Parafurnalia 3: The Furry Code

Parafurnalia explores the many and various media that comprise our shared furry history—one thing at a time. Give Chipper a shout if you have a furry-related object, document, puppet, forgotten room party sign, tiny little sticker, huge scroll of paper, etc., that you think would be neat to feature!

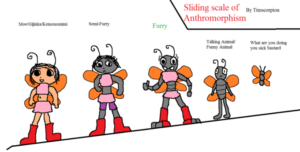

For as long as the fandom has been around, furries have been interested in degrees of furry-ness – just how furry you are, inside and out. For instance, the alt.fan.furry newsgroup offshoot, alt.lifestyle.furry (ALF), was formed in 1996 for those who felt furry wasn’t just a hobby but was an inextricable part of themselves. Late 90s and early 00s flame wars on Usenet, IRC chat, and online forums were fought over the limits of furry — whether it was okay for furry to be an identity, a lifestyle, a sexuality. Various surveys, from the Furvey to the Furry Survey to Furscience studies, give furries the chance to rate and evaluate their relationship to furry and fandom identity. And of course, we can’t forget the many versions of the Furry Scale:

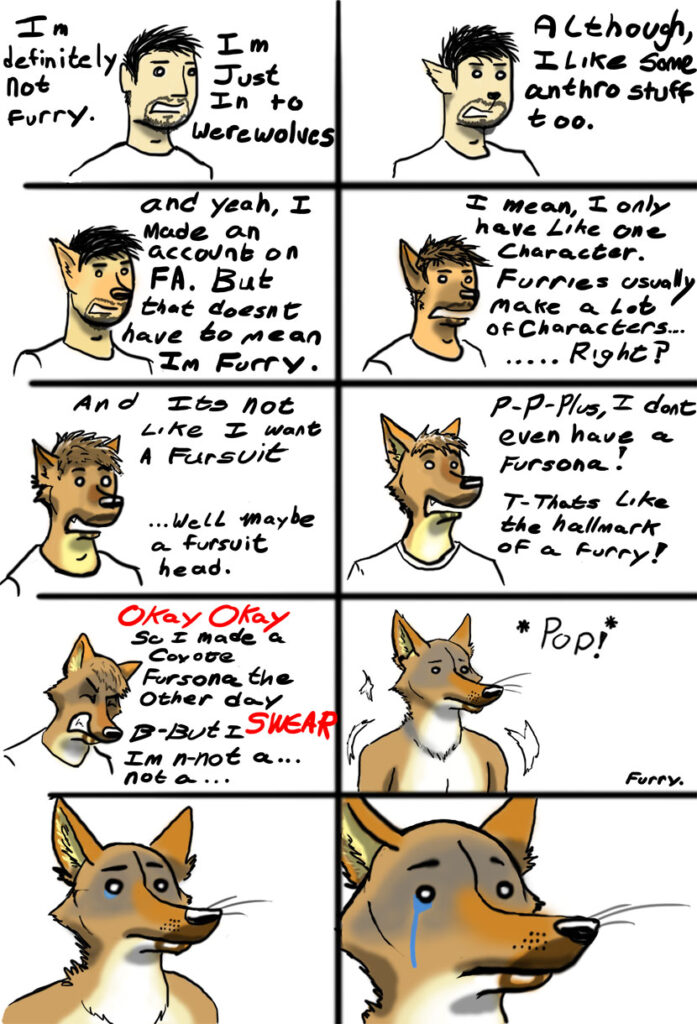

The notion of a furry scale raises perennial questions about the power and limits of furry identity. Where do our human selves end and our furry selves begin? Or, are they inherently intertwined? Is furry something we’re born with or something that develops by being exposed to The Lion King or Zootopia or Robin Hood at a young age? Can you get more (or less) furry with time and age? What would it mean to live an unabashedly furry life — indeed, to become your ‘sona? Furscience has shown that furries run the gamut from identifying as fully non-human to fully human, as well as from seeing their fursonas as external characters to seeing them as their true selves (“Research Findings,” see in particular 3.11, 4.1, and 7.2). The beauty of furry is that you get to make it your own. Yet it’s important to note, for the historical record, that these questions regularly recur — and have regularly sparked debate — in the many discourse spaces that furries have called home, from FurryMUCK and alt.fan.furry, to FurAffinity and Second Life, to Twitter and Bluesky.

Native New Zealander Ross Smith’s 1996 Code of the Furries, a.k.a. the Furry Code, was one of the earliest versions of a furry scale, and its purpose was to help furries express themselves and make the fandom their own. Offering a shorthand for identifying one’s relationship to various aspects of the fandom, it looked something like this (Smith’s own code):

FRM/R4 A+++ C+++ D++ H+++ M+++ P++++ R+ T++++ W Z++++ Sm++

RLCT a+ cn++ d++ e+ f++++ h+ j iwf+++ sm

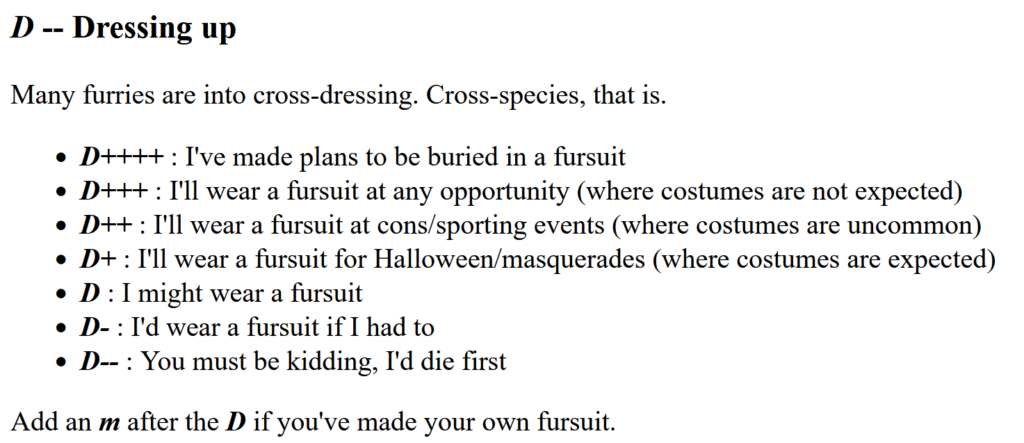

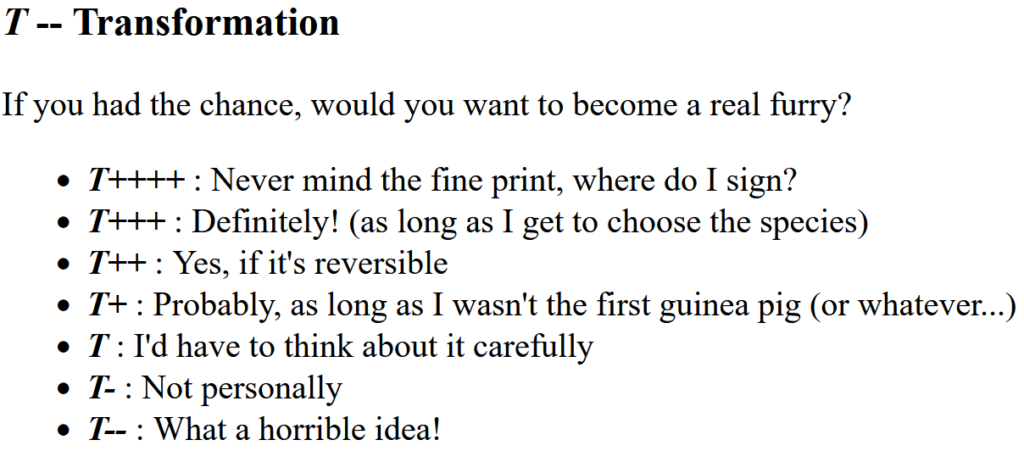

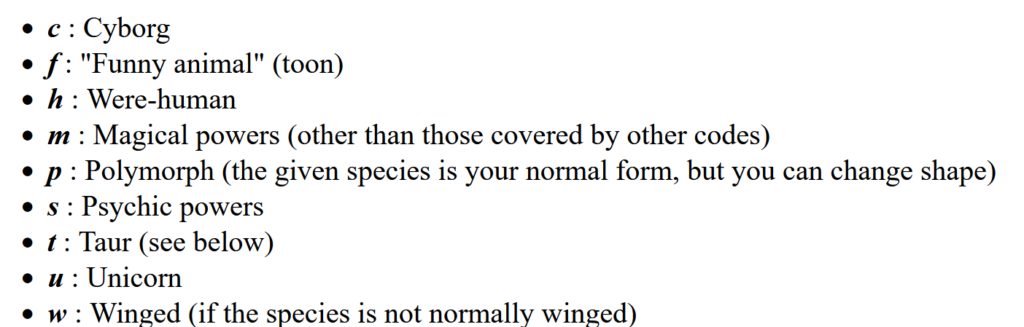

The code is divided into two halves, the first half (top line) covering one’s furry side and the second half (bottom line) covering one’s human side. Each letter (or letter grouping) designates different aspects of one’s identity. The first grouping (“FRM/R4” in this example) is a way of designating your fursona, broken down by family and genus/species. Thus, “FRM/R” translates roughly to “Furry – Rodentia – Mouse/Rat.” The number signifies “where you fall on the human-to-animal scale,” with 4 translating to “equally comfortable on two or four legs (or, if you’re a taur, on four or six).” Following that, the upper-case letters A-Z designate categories having to do with one’s furry self, and following each letter is a number of plusses or minuses to designate degrees of identification within that category. Here are a couple totally random and definitely not preselected examples from Smith’s guide:

Categories include (A)rt, (C)onventions, (D)ressing up, (H)ugs, (M)ucking and mudding, (P)lush critters, (R)ealism and tooniness, (T)ransformation, (W)riting, (Z)ines, and Furry (S)ex.

The second half of the string begins with another set of upper case letters. “RL” — Real Life — designates a line of work. “RLCT,” in this case, stands for “Real Life – Computers/information technology.” And the lower case letters that follow are about “Your human side,” including (a)ge, (c)omputers, (d)oom [for Doom, Quake, and other early first-person shooters], (e)ducation, real life (f)urriness factor, (h)ousing, (i)nternet, (j)apanese animation (i.e., anime), (p)ets, human (s)ex.

Smith specifies that you can create your code using as few or as many categories or as you wish. It’s not about pushing past your comfort zone, but rather finding the language to “delurk” (a familiar sentiment 30 years later). In addition, there are modifiers. “?” means “you haven’t decided where you fall in that category”; “!” indicates “a positive refusal to participate in this category”; and “#” means “you prefer to keep this information to yourself.” There are also category-specific modifications. After your fursona, for instance, you can add the following:

Like furry itself, you get the make the code your own. As Smith says in the introduction section, “As with all such codes, the idea is to produce a series of compact symbols that (a) communicates our essential characteristics to other members of our subculture, and (b) looks really cool.” Although furry codes didn’t last long — one rarely finds them in the 2000s, except in the occasional signature line — they give us a lens into what furry identity meant in the mid-to-late 90s. Categories like tooniness, TF, and plush critters have only gotten more popular. Zines and MUCKs, by contrast, aren’t so common anymore – even less so Doom and Quake, though as Smith notes, these games “seem to be at least as hugely popular among furries as they are among the population at large.”

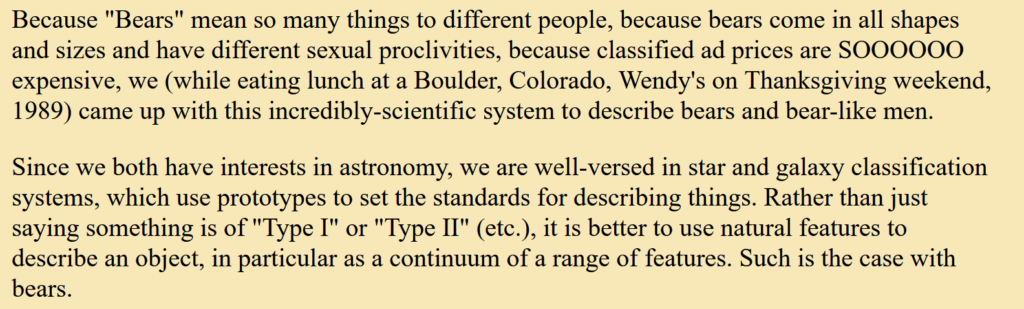

Smith’s “As with all such codes” is telling, too. As he explains, the Furry Code was inspired by Robert Hayden’s 1993 Geek Code, Peter Caffin’s 1996 Goth Code, and Jayne Alexander and Dave Ratcliffe’s 1995 Cat Codes (adapted from Eric Williams’s original). These codes, in turn, were inspired by Bob Donahue’s and Jeff Stoner’s 1989 Natural Bears Classification System — a.k.a., Bear Code — which appeared around the same time as the Smurf Code and Kirk Johanning’s Twink Code. But wait, there’s more! Donahue and Stoner explain how the Bear Code was inspired by astronomical systems for describing stars:

The idea of using natural features to describe oneself (rather than “types”) points to something really important about these various early-internet-era codes. In the Wild West days of the internet, these codes, first of all, made it possible for folks to see what they had in common and what made them different — to build the foundations of community. The Goth Code, for instance, includes 20 “Types,” such as AntiquityGoth, FetishGoth, TrashyGraveyardGoth, CybertechGoth, and GlitterGoth. While such categories were meant to signify commonalities, string the various categories together and you create your own unique set of characteristics. As for the furry code, a glance at someone’s signature line and you could easily see which aspects of the fandom or real life you had in common. It’s not so different from how we treat social media profiles today, except that you could fit quite a bit more information into roughly the same amount of space!

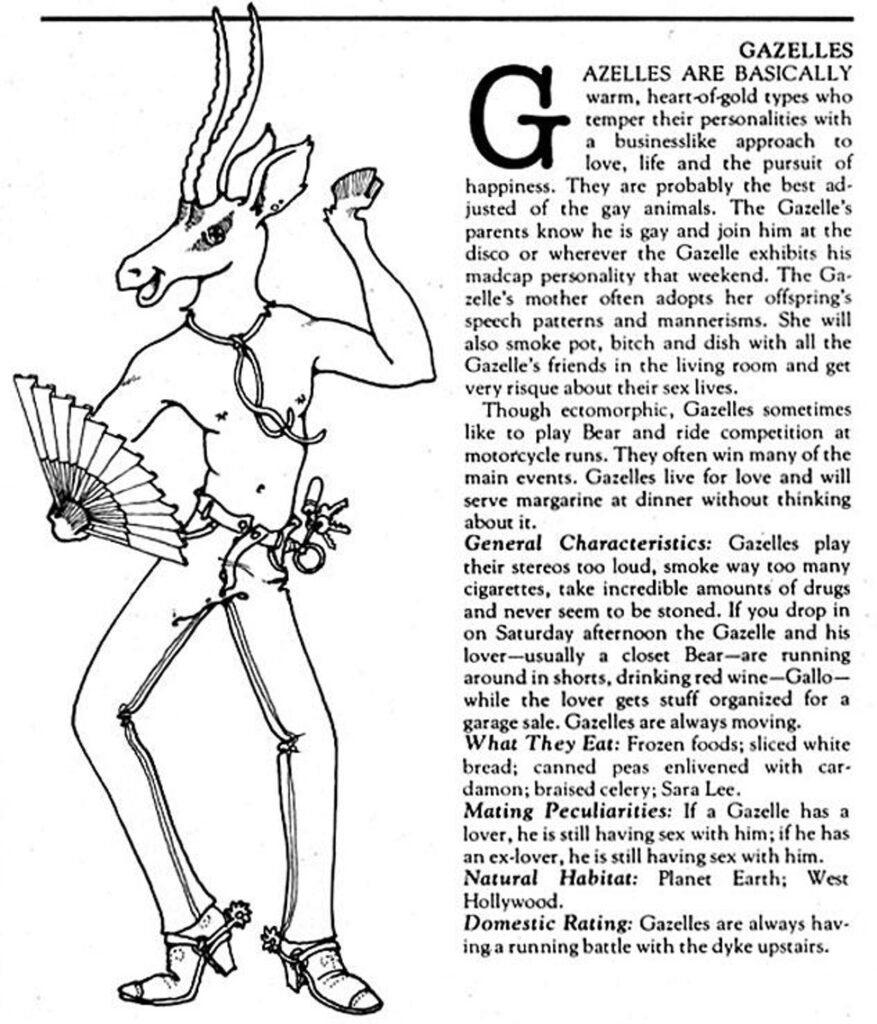

Second, because the codes were an efficient way of describing your appearance and interests, they were crucial to the burgeoning gay/queer internet. As one Reddit user puts it, “Back in the day, we couldn’t send pictures on chat/dating sites so we sent out our stats and had to imagine what the guy looked like.” References to the Smurf and Bear codes appear all over the Usenet archives for the newsgroup soc.motss (“soc” being the top-level hierarchy for social and cultural newsgroups, and “motss” meaning “members of the same sex”) starting in 1990 and alt.sex.motss starting in 1991. According to writer and technologist David Auerbach, soc.motss, founded by Steve Dyer in 1983 as net.motss, was “The First Gay Space on the Internet.” Queer internet historian Avery Dame-Griff writes that “For some posters, net.motss was the first place where they felt comfortable coming out as gay.” And going still further back in time, we might draw a link to George Mazzei’s and cartoonist Gerard Donelan’s 1979 Advocate article, “Who’s Who in the Zoo” (itself a reference to a WW2-era Looney Tunes cartoon), which classified gay men and women as various zoo animals.

In an interview, Bennie tiger pointed out that these codes amounted to “a digital version of a hanky code,” the system of using handkerchiefs to signify sexual preferences and interests that was developed in the 1970s (Bennie tiger, interview). As Uncle Kage poignantly put it in a 2023 interview with me, “This was a period in American history where a young person, upon realizing they were gay, was faced with the necessity of life of absolute loneliness. You could NOT express yourself. Could NOT look for companionship” (Kage, interview). So it might not seem like much, but a simple code that let you express yourself could be the difference between lurking as a total unknown and making a friend or partner.

Which brings us back to the Furry code. Under the category of “Furry Sex,” Smith writes, “Like it or not, S-*-X seems to be part of furry life.” The furry code appeared at a time when flamewars were heating up over furry lifestyle and sexuality. In a late 1994 Usenet thread called “What Is Wrong With Furry Fandom Today,” one discontented furry claims that “that furry comics today are little more than all out furry fuck-fests.” As for furry fans, the user says, “[G]row up. […] Too many potential fur fans are scared off by what I can only consider degenerates living in a fantasy world in furdom today. These people probably wear fake tails to job interviews for crying out loud!” (Henderson). Numerous lengthy alt.fan.furry threads from 1996-97 involve numerous users lamenting the “direction” that furry was going (an early version of the “I wish things could go back to how they were” argument).

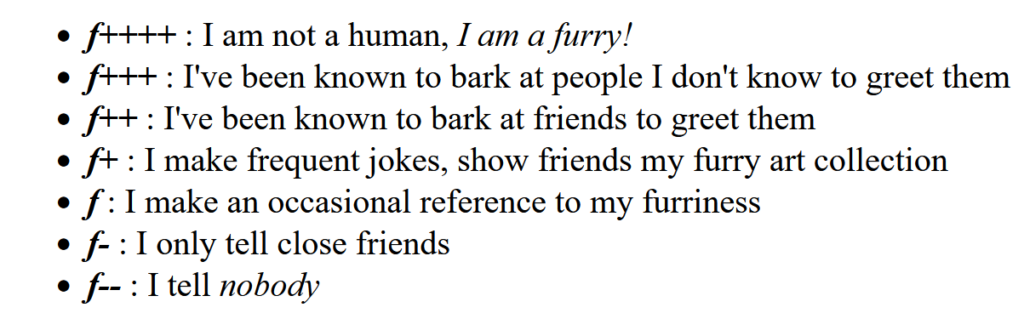

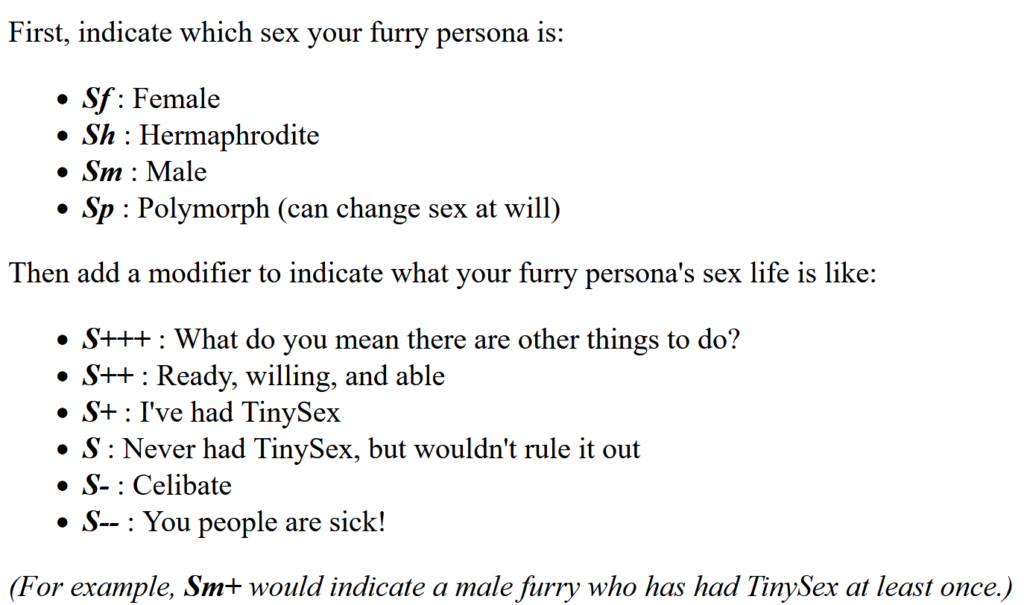

One of the neat things about the furry code, then, was how it gave folks the chance to provide details about their relationship to furry lifestyle (f) and furry sex (S) without any pressure to do so. Here are the codes for each.

(Note: TinySex, or TS, was cybersex that took place primarily on TinyMUDs and MUCKs. Notably, Smith’s code appeared at the same time that, on FurryMUCK, a document was being circulated called “A Beginner’s Guide to TinySex on the FurryMuck.”)

Aside from the fact that the furry code was accessible and inviting, Smith allowed the code to be freely distributed, meaning that it ended up on lots of folks’ websites. Captain Packrat was one of the first to host it and remains the longest-running. “I offered to host it because I was running my own webserver and had plenty of space available. I hosted a number of small websites for various people at the time.” (Captain Packrat, interview). And of course, after the code had gathered enough momentum, furries – always the clever ones – invented decoders for the furry code, so that you can simply plug in someone’s code and have it spit out the translations.

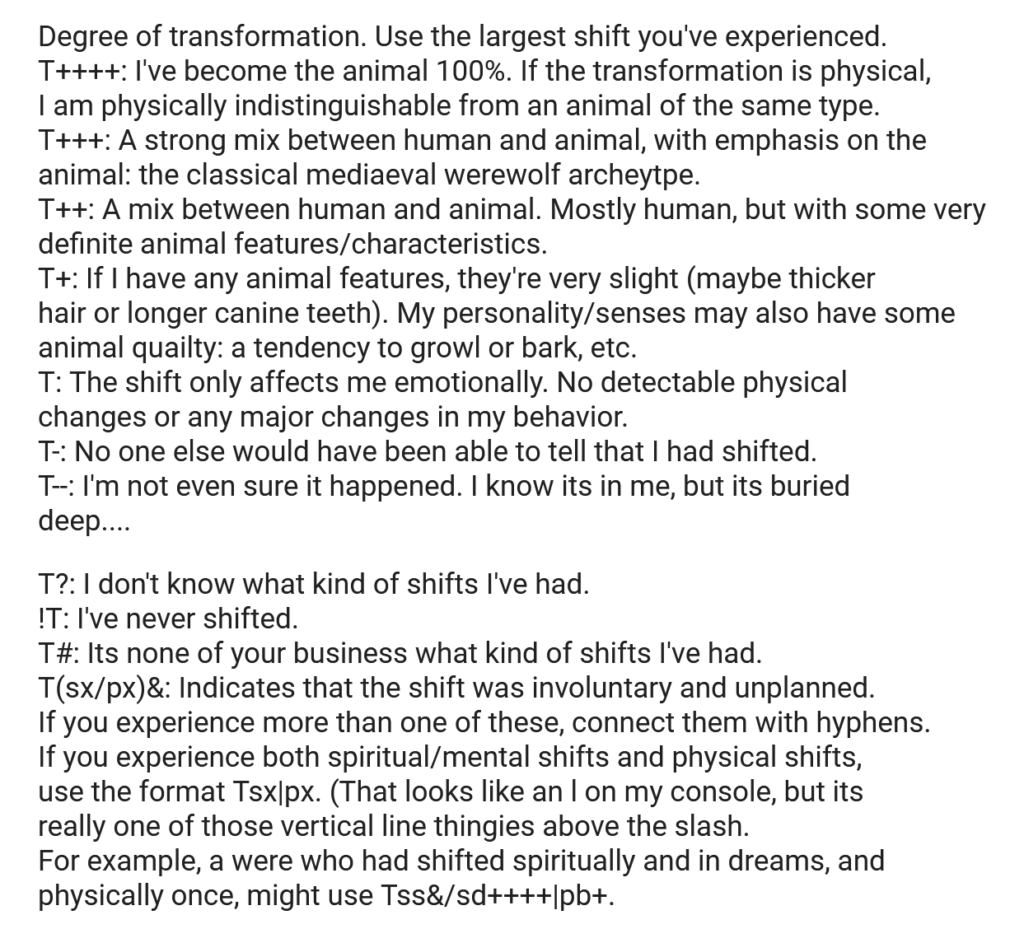

Additionally, as furry sub-communities formed, the furry code inspired some interesting offshoots. Locandez fox, who is credited with creating the Furvey (furry survey), also created the Yiff code and had started working on a Furry Lifestyle Code. On the well-known Usenet group alt.horror.werewolves, user Blackfang proposed a WereCode that allowed weres to share their phenotypes, how often they went to howls, other weres they’d met in real life, and most importantly, TF preferences:

Although the Furry Code fell out of use in the early 00s as Usenet gave way to other furry haunts such as IRC and Second Life, it’s a fascinating snippet of furry history. I was sadly unable to reach Ross Smith in the writing of this article, but I clasp my paws for the keen fur who made it a little easier to delurk and to be your best furry self.

Here is a link to the Code as it appears on Captain Packrat’s website — unchanged since 1998 — if you want to work out your own furry code!

Works Cited

Auerbach, David. “The First Gay Space on the Internet.” Slate. August 20, 2014. <link>

Bennie tiger. Personal interview (Telegram). January 9, 2025.

Blackfang. “Proposal: WereCode v.0.5.” Alt.horror.werewolves thread. September 29, 1996. <link>

Captain Packrat. Personal interview (Telegram). January 3, 2025.

Dame-Griff, Avery. “Love, Acceptance, and Screeching Modems.” Spark: the Magazine of Humanities Washington. June 6, 2023. <link>

Donahue, Bob, and Jeff Stoner. “Resources for Bears: The Bear Codes.” Version 1.0. November 23, 1989. <link>

Furscience. “Research Findings.” The International Anthropomorphic Research Project. Accessed January 5th, 2025. <link>

Henderson, Brian. “What Is Wrong with the Furry Fandom Today.” Alt.fan.furry thread. December 13, 1994. <link>

Mazzei, George (author) and Gerard Donelan (illustrator). “Who’s Who in the Zoo: A Glossary of Gay Animals.” The Advocate. July 26, 1979. <link>

Smith, Ross. “The Code of the Furries.” Version 1.3. February 7, 1998. Hosted by Captain Packrat since 1998 <link>. Archived from the original <link>.

Uncle Kage. Personal interview (Discord). April 13, 2023.

This certainly hit me in the memory bank. I remember taking so much time to get my code figured out and deciphering others’ codes. Something I wonder now, however, is the extent to which this needing to code oneself and identify on a scale or “degree” of “furriness” comes haunted/informed by genealogies of psycho-medical discourse, fans using diagnosis in a reparative way.

That is an interesting point. Indeed, I wonder if genealogies of psycho-medical discourse played into the creation of several/all of the various codes that were developed and that were in conversation with one another in the late 80s and early 90s? On the one hand, the codes could provide a discreet way of signaling one’s identity and interests. On the other, the very *need* for discretion (in queer/gay communities) points to the legacies of medicalizing discourses.

Thank you Chipper for writing about a subject that many people in the fandom have likely never seen and even greymuzzles may have forgotten. I hope Ross Smith is still out there and being his best furry self.

What a fun read!! Had to get out a pen and paper to have a go at making my own code ^w^ Great work as always Chipper

Eee tysm Shwahb!! :DD I know, it’s honestly a fun little exercise. I wonder what categories would be added in this day and age?